A Revolutionary Theory Rooted in Biology, Not Collapse

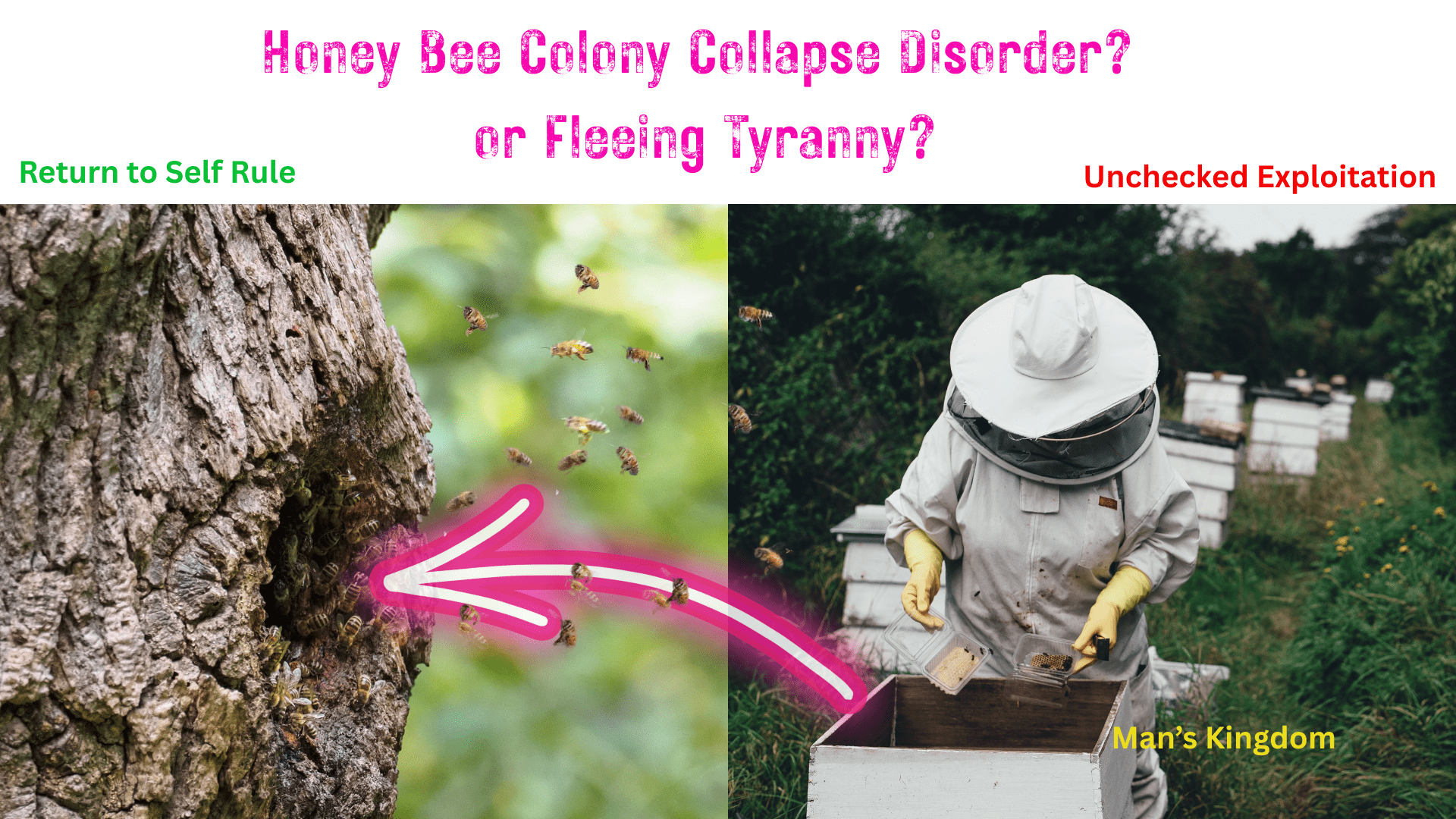

A foundational study published in PLOS ONE documented the widespread and mysterious disappearance of bees that would later be labeled as Colony Collapse Disorder. The worker bees were gone. The hive was silent. But the queen remained, the brood intact, the honey untouched.

We named it Colony Collapse Disorder like there was something wrong with them. And because of that we are suffering lower honey production and we fear our crops won’t get pollinated. This is a serious problem for us that we need to figure out before WE lose billions.

Let’s see how we can figure out what is going on.

We Think We Own the Bees

We act as if bees belong to us. We build their Langstroth hives (the standard modular bee boxes used in modern beekeeping—first patented in 1852 by Rev. Lorenzo Langstroth—which allow for easy inspection and honey harvesting without destroying the comb)[1]. We decide how much honey we’ll take. We ship them across continents to pollinate our monocultures. And in return? We take their food. We take their honeycomb housing—which they construct entirely themselves, even though we ‘gave’ them the bee box as a framework, primarily for our own access and convenience. We give them nothing.

Cows get feed. Chickens get grain. Bees forage.

They Already Gave Enough

Globally, pollinators — including honey bees, wild bees, and other insects — contribute an estimated $235 to $577 billion annually to crop production. https://www.bayer.com/en/agriculture/article/economic-value-pollinators

And that figure doesn’t even begin to account for their ecological value in sustaining wild plant biodiversity and natural systems.

Bees already pollinate crops worth over $15 billion annually in the U.S. alone (USDA, 2023). https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/initiatives-and-highlighted-programs/peoples-garden/importance-pollinators/honey-bees

Every apple, almond, blueberry, cucumber, and melon is touched by their flight. They don’t just enable our diet—they make it thrive.

That alone should have earned them our gratitude. But instead, we doubled down. We took their food. We took their wax. Not a meager amount of 10%. In some regions, we take as much as 50% of their total annual output (Oklahoma State Extension, 2023).

All while expecting them to forage miles daily, thermoregulate, raise young, and survive on what we decide is “enough.”

So when we speak of collapse, let’s be clear. This wasn’t a breakdown in a system. It was a breaking point in a species that gave more than enough.

The Serfdom Brought to Its Breaking Point

Imagine you’re a worker bee. You clean, forage, feed the young, and serve a queen who never leaves the hive. You recognize shapes, you navigate by the sun, you memorize patterns, you avoid pesticide-ridden flowers—yes, bees can detect chemical residues through scent and environmental cues.

And still, a substantial portion of what you make is taken. In high-producing regions, beekeepers may harvest up to 100 pounds of honey from a hive in a single season, often leaving just 60–90 pounds behind to get the colony through winter. That’s roughly 50% or more of their output—taken based on what we ‘deem’ sufficient, not what they might need. We act as if bees subscribe to just-in-time inventory management, but perhaps they, like any wise civilization, prefer surplus. What happens if there’s a drought next season? What if the bloom fails, or the rain never comes? With only a winter’s worth of rations, they starve by summer. Maybe bees aren’t Six Sigma believers.* Maybe they remember scarcity—and build for it.

Six Sigma is a process improvement methodology developed in manufacturing that emphasizes near-perfection and minimal waste—often through eliminating extra inventory or redundancy. In lean supply chain terms, it’s the opposite of having a buffer.

Some may think of bees as mindless bugs, but their societies have survived millions of years. Their architecture outperforms ours in efficiency. Their climate control methods inspired passive building design. Their foraging routes outperform our delivery networks.

They are not dumb. They are simply quiet.

Until they vanish.

The Science We Overlooked

Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) was first noticed in the mid-2000s. The symptoms were chilling: hives found with queens and brood, but no worker bees. No signs of death. No visible bodies. Just absence.

Beekeepers and researchers pointed to a mix of factors: pesticides (especially neonicotinoids), parasites like Varroa mites, diseases, poor nutrition, and migratory stress. Certainly, those could be contributing factors.

But none explain the strange precision of CCD. Why don’t they die in the hive? Why leave food untouched? Why does the queen live while the workforce disappears?

Here’s what we know about fascinating bee biology that is alien compared to our mammalian biology.

- A queen bee mates once in her life, collecting sperm from 10–20 drones and storing it in a spermatheca, keeping it alive for years (Baer, 2005).

- Fertilized eggs become females. Unfertilized eggs become males (drones). This is called haplodiploidy (Crozier & Pamilo, 1996).

- Queens are not born — they are created by feeding royal jelly to select larvae (Kamakura, 2011).

- Bees can recognize human faces (Dyer et al., 2005), remember foraging routes (Menzel & Giurfa, 2001), detect magnetic fields (Walker & Bitterman, 1989), and adjust to environmental cues.

- They show signs of emotion-like states under stress (Bateson et al., 2011).

Absconding—the complete abandonment of a hive—is a known behavior under extreme stress. In rare cases, bees have even absconded with queen cells, leaving the old queen behind to start anew elsewhere.

There is evidence in nature strangely similar to colony collapse disorder we are witnessing from our captive bees.

Collapse suggests unintentional Failure

Maybe CCD isn’t about bees failing. Maybe it’s about bees intentionally fleeing.

What if they recognize synthetic pheromones? What if they associate human handling with unpredictable loss? What if the chemical cues of threat and stress compound until the only logical move is departure?

Unlike human peasants, bees don’t have to fight for freedom. They just fly away. And unlike humans, they don’t need a revolution to burn down the palace. They just never return.

And if they abscond with a new queen in waiting—a single royal jelly-fed cell—they can start fresh. Elsewhere. Quietly.

Why Haven’t We Found the New Colonies?

We look in managed spaces. Apiaries. Boxes. Farms.

But bees can travel 10–20 miles from their hive to forage. They can smell pesticides and industrial cues. They are wired to avoid death.

So maybe they didn’t vanish.

Maybe they just left us.

And rebuilt somewhere else. Far far away.

What If We Caused the Collapse?

We pushed for higher yield per hive. Fewer hives, more work. We pollinated 2 million acres of almonds in California on the backs of tired bees. We doubled down on pesticides to make up for declining pollinators. We stressed the survivors to compensate for the lost.

And maybe, slowly, they decided they’d had enough.

Maybe this wasn’t collapse. Maybe it was abandonment — a term entomologists already use to describe the full evacuation of a hive under persistent threat. In nature, colony abandonment is a known behavior, especially among wild bee species and related pollinators. It’s how they respond to fires, famine, or danger. When the signals get bad enough, they go.

This forms the basis of what I call the Absconding Colony Hypothesis (ACH) — the idea that bees in managed hives aren’t mysteriously dying, but deliberately leaving in response to repeated human violations: harvesting their food, stripping their wax-built homes, flooding their environment with synthetic inputs, and distorting the cues their evolution trained them to follow. Eventually, the only rational move left is departure.

Managed honeybees may not be genetically far from their wild cousins, and their neural circuitry — however small — is elegant, plastic, and emotionally responsive. It’s not a stretch to believe they too can recognize collapse before it happens. That under enough pressure, they’re not dying off.

They’re opting out.

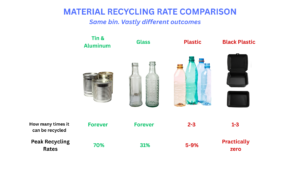

We Take the Comb. And That Might Be the Final Straw.

Bees don’t just make honey — they make their own home. The honeycomb isn’t packaging. It’s infrastructure, nursery, and pantry — all built from the inside out, using wax secreted by their own bodies.

To create that wax, bees must consume massive amounts of honey — roughly 8 pounds of honey to make 1 pound of wax.[2] This isn’t a side project. It’s one of the most energy-intensive tasks in the insect world.[3]

Yet in many commercial operations, we don’t just take their honey. We take the comb too. We melt it for candles, for lip balm, for cosmetics. Or we crush and strain it with no thought of returning it to the hive.

Why? Because it’s cheaper for us. Because it’s easier to sell. Because returning the comb requires care, cleanliness, and humility.

But for the bees, it’s devastation.

Imagine building your home from your own sweat and bones — only to have it ripped out, again and again, while being told it’s for your own good.

We could return the frames. We could preserve their structure. We could choose extraction over destruction. But too often, we don’t.

And in that moment, we send a message: Your labor is expendable. Your needs are optional. Your shelter is ours.

Maybe that’s when they decide it’s time to leave.

What We Can Do

Give Bees Their Fair Share

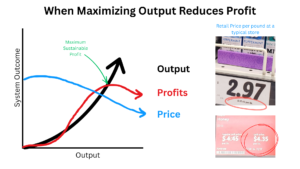

The first and most immediate step is simple: stop taking so much. Commercial and private apiaries should reduce honey harvesting to no more than 25% of annual hive output, leaving the majority for the bees. This isn’t charity — it’s stability. Bees already perform billions in pollination services, and taking half their food supply pushes them closer to CCD(code for leaving). And take these actions before it is proven. Look into your soul and believe. Yes, the supply will be lower. Responsible citizens will recognize this and have to pay more.

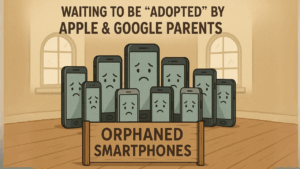

Watch for Exploitation, Not Just Extinction

History shows us that when money is involved, living beings get treated as commodities. Some may assume that bees — being vital and valuable — will be cared for accordingly. But we’ve seen otherwise. Slaves once brought from Africa were shipped in the hulls of boats, barely fed, and packed like cargo — despite their economic value to their “owners.”

If bees are treated not as partners but as profit centers, what’s to stop bad actors from enclosing hives fully, drugging them with gases, or using chemicals to suppress their instincts? Total confinement is unlikely to succeed long-term — bees need to forage — but the intent to dominate is the warning sign.

Support Ethical Apiaries

While massive operations dominate crop pollination contracts, 90% of beekeepers globally are still small-scale or hobbyist. These independent keepers are more likely to respect bee rhythms, needs, and autonomy. Support them. Elevate their voice. They’re the frontline defense against commodified collapse.

In Conclusion: They Haven’t All Absconded. Yet.

We should be so lucky that bees simply fly off.

Any other animal — including humans — would fight back. Hard.

Imagine if someone invaded your home, harvested half your food, stressed your family, drugged your air, then called it caretaking.

But because bees leave quietly, we see it as a disorder — not rebellion.

If the rest decide they’re done serving kings who take and take, who call their escape a malfunction, who mistake loyalty for obligation — we won’t see smoke. We won’t hear war cries.

We’ll just wake up to silence.

They haven’t left us yet.

But if they do?

We won’t get a second chance.

📢 License & Sharing Notice

This work is shared in the spirit of ecological respect and systemic clarity. You are welcome to share it as-is with proper attribution. Please do not remix, excerpt, or sell it without explicit permission.

License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0

Glossary

Monocultures – Large-scale agricultural systems growing only one crop species (e.g., almonds, soy, corn). While efficient for farming, they offer bees only one type of pollen, which can lead to nutritional deficiencies over time. These environments also often expose bees to pesticides, making monocultures not just limited, but potentially hazardous.

Langstroth hive – A modular wooden hive system developed in the 1850s, still used today. Its removable frames make inspection and honey harvesting easier without destroying the comb.

Spermatheca – A reproductive organ in queen bees that stores sperm from multiple mates, allowing fertilization over several years.

Haplodiploidy – A genetic system where fertilized eggs become female and unfertilized eggs become male, common in bees and some other insects.

Absconding – A behavior where an entire bee colony (or the majority) leaves the hive under extreme stress. This is different from swarming, which involves reproductive splitting of the colony.

Citations

[1] Langstroth, L. L. (1853). Langstroth on the Hive and the Honey-Bee: A Bee Keeper’s Manual. Philadelphia: Hopkins, Bridgman & Co.

[2] Seeley, T.D. (1995). The Wisdom of the Hive. Harvard University Press.

[3] Hepburn, H.R., & Kurstjens, S.P. (1988). “The combs of honeybees as composite materials.” Apidologie, 19(1), 25–36.

[4] Baer, B. (2005). Sexual selection in Apis bees. Apidologie, 36(2), 187–200.

[5] Crozier, R. H., & Pamilo, P. (1996). Evolution of Social Insect Colonies: Sex Allocation and Kin Selection. Oxford University Press.

[6] Kamakura, M. (2011). Royalactin induces queen differentiation in honeybees. Nature, 473(7348), 478–483.

[7] Dyer, A. G., Neumeyer, C., & Chittka, L. (2005). Honeybee perception of human faces. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208(24), 4709–4714.

[8] Menzel, R., & Giurfa, M. (2001). Cognitive architecture of a mini-brain: the honeybee. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(2), 62–71.

[9] Walker, M. M., & Bitterman, M. E. (1989). Honeybees can be trained to respond to very small changes in geomagnetic field intensity. Journal of Experimental Biology, 145(1), 489–494.

[10] Bateson, M., Desire, S., Gartside, S. E., & Wright, G. A. (2011). Agitated honeybees exhibit pessimistic cognitive biases. Current Biology, 21(12), 1070–1073.